Predictive policing

For well over a century, police have attempted to find ways to predict where, when, and by whom crime is going to be committed. In the 21st century, this ambition often takes the form of predictive algorithms that use historical data in an attempt to anticipate future events. Police often plug in events as disparate as traffic information, crime statistics and incident reports, or even the grades of school children. The algorithmic outputs often guide police procedure, patrols, and even who to put under increased surveillance.

But of course, police cannot actually predict crime, with or without a computer. Nobody can see the future. What police can do, however, is make assumptions about who and where crime is most likely to occur and put those places and people under intense scrutiny. Such heightened surveillance can lead to increased traffic and sidewalk stops, documentation of a person’s activities over time, and even use of force.

Predictive policing is often a self-fulfilling prophecy. If police focus their efforts in one neighborhood and arrest dozens of people there during the span of a week, the data may reflect that area as a hotbed of criminal activity, leading the algorithm to deploy more officers there the following week. The system also considers only reported crime, so neighborhoods where the police are called more often might see predictive policing technology concentrate resources there. This system can aggravate existing patterns of policing–especially in neighborhoods with concentrations of people of color, unhoused individuals, and immigrants—by using the cloak of scientific legitimacy and the supposed unbiased nature of data.

How it works

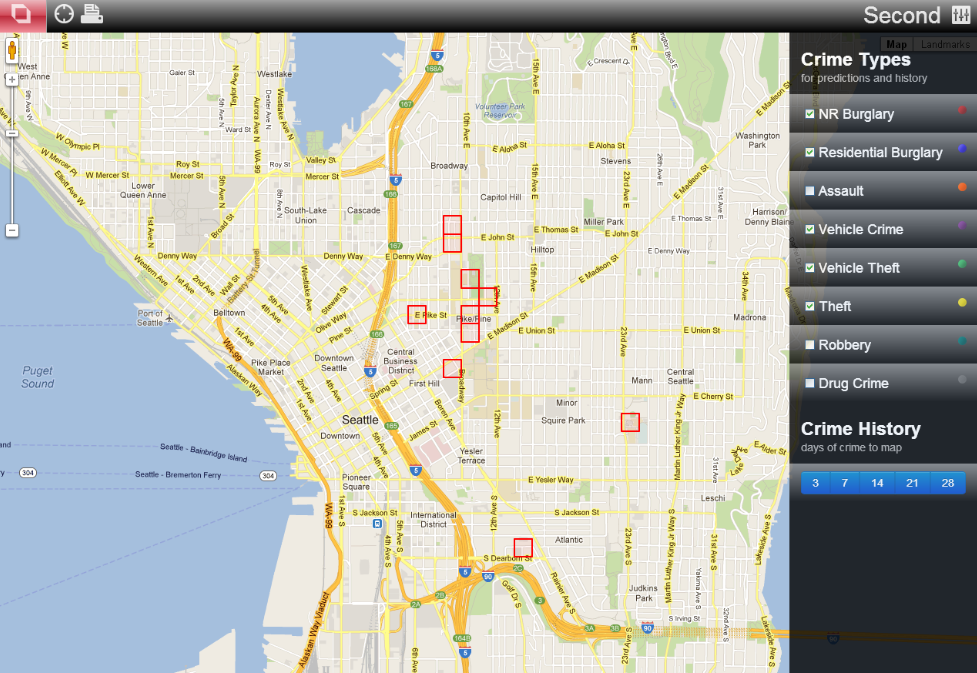

Predictive policing programs generally work by feeding crime data, and sometimes massive amounts of other data, into an algorithm which tries to look for unseen patterns which can reveal where and when crimes are most likely to take place. That information can include, for instance, the locations of all crimes recorded by police, the time at which they were committed, or even the weather. The predictive model can shape deployment of patrols.

In some cases, programs like these can focus on individuals. In Pasco County, Florida, police assigned a point system to individuals based on factors like a family’s income bracket or grades in order to assign a level of likelihood a child is to commit crimes–and then harass them and their family.

How Law Enforcement Use It

Law enforcement often claims that predictive policing is a “force multiplier,” something that allows departments to allocate officers and resources more strategically. This means that police feed data into software which identifies patterns which police hope will dictate where they should deploy officers in order to prevent criminal activity. This can take the form of “heat maps” that display city blocks that supposedly will have higher-than-normal crime levels, followed by “cops on the dots” deployment of officers to such blocks.

Who Sells It

PredPol, now named Geolitica, was an early predictive policing vendor. It began a pilot program in the Santa Cruz Police Department in 2011. By 2020 some police departments began canceling their contracts amid public concerns over civil liberties. Los Angeles ended its subscription. Santa Cruz and New Orleans banned the use of predictive policing algorithms altogether (although New Orleans has since rolled back these protections).

In 2018, it was reported that Palantir, a company that often tries to help agencies organize and visualize large sets of data, was testing a predictive policing system in New Orleans without the knowledge of elected officials. Banjo, which briefly held a multi-million dollar contract with the state of Utah, was eventually found by a government audit to be incapable of providing the services it had offered the state and was given access to state databases which contained sensitive information.

Some police departments work with vendors to build their own version of this tool, like the NYPD/Microsoft Domain Awareness Systems. Also, vendors known for other types of surveillance technology are getting into the predictive policing market. In 2018, ShotSpotter, a company that sells acoustic gunshot detection, acquired a company called HunchLab in the hopes of telling police where gunshots might happen in the future.

Threats Posed by Predictive Policing

For at least a century, police departments have been using statistics and mapping in an attempt to understand where and when crime might occur, but the challenges proposed by digital technology pose new civil liberties threats. No one should have their constitutional rights abated because they live in or walk through areas where an algorithm has predicted there will be crime.

There are also major concerns about the type of data being fed into these programs. More and more types of sensitive personal data about individuals are being fed into these programs. There also is the larger problem of skewed data generated by police departments. For instance, if police put majority Black neighborhoods under intense police scrutiny and surveillance, they will be more likely than in other neighborhoods to make stops and arrests according to minor quality of life infractions. Therefore, derivative maps purporting to show where future crimes might be committed will disproportionately weigh those neighborhoods already living under the weight of intense police presence. This can create a self-fulfilling prophecy that uses the supposed objectivity of math to legitimize racially biased police procedures.

Police agencies and vendors also claim they can train machine learning algorithms to predict whether a person is likely to commit crimes. A particularly dubious claim is that this can be done by analyzing physical attributes of al person’s face.

EFF’s Work Related to Predictive Policing

Because of the risk it poses to civil liberties and vulnerable populations, EFF advocates for bans on predictive policing. We also cheer on lawmakers who want to take a more active role in probing predictive policing vendors and police departments. We will continue to support law makers towns, states, or national governments in their attempts to rein in this dangerous technology.

Suggested Additional Reading

Predictive Policing Software Terrible At Predicting Crimes (The Markup)

“Bang!”: ShotSpotter Gunshot Detection Technology, Predictive Policing, and Measuring Terry’s Reach (Journal of Law Reform)

Predictive policing algorithms are racist. They need to be dismantled. (MIT Technology Review)

How the LAPD and Palantir Use Data to Justify Racist Policing (The Intercept)