Gunshot detection

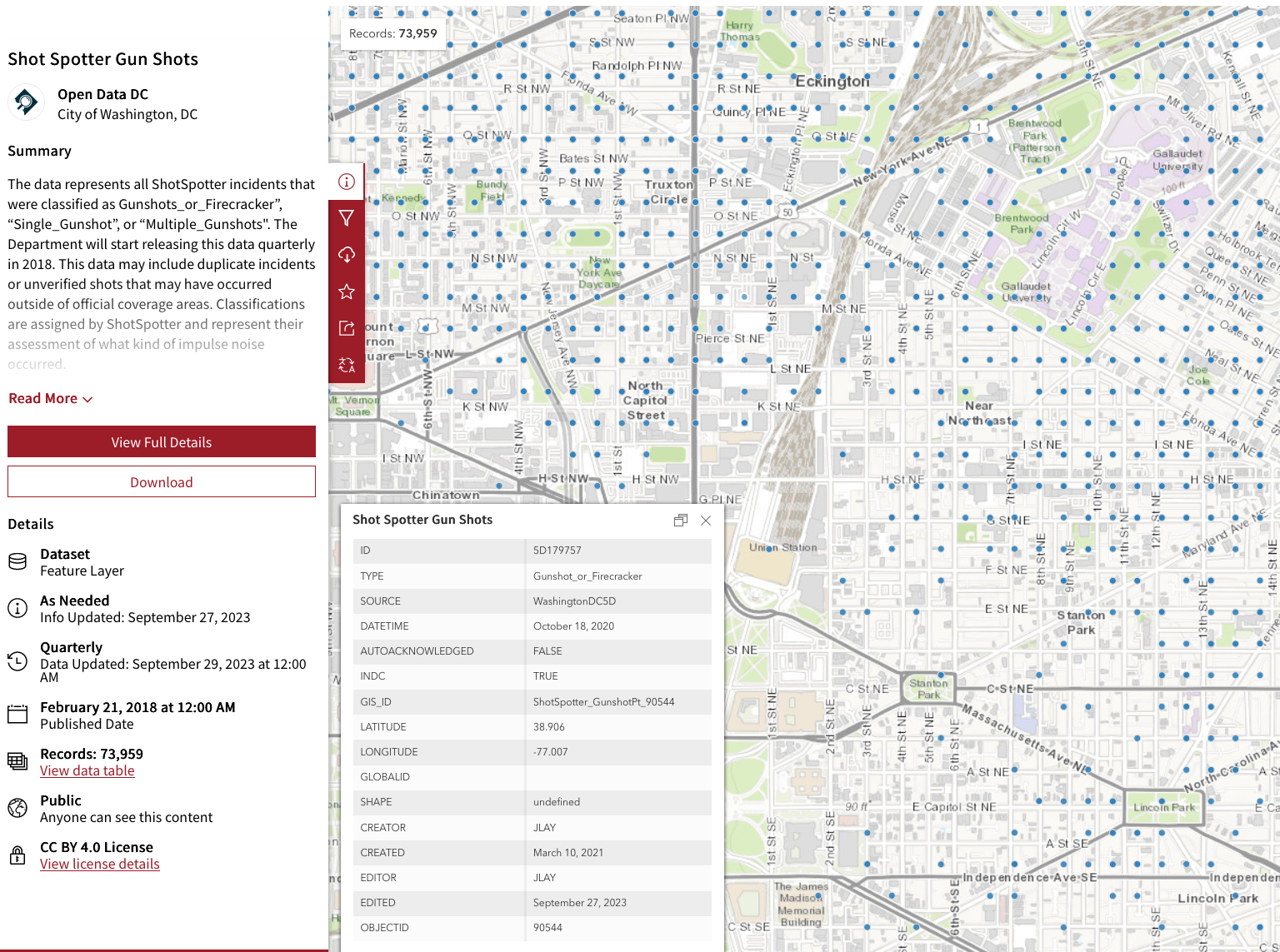

Acoustic gunshot detection is a system designed to detect, record, and locate the sound of gun fire and then alert law enforcement. The equipment usually takes the form of sensitive microphones and sensors, some of which must always be listening for the sound of gunshots. They are often accompanied by cameras. They are usually mounted on street lights or other elevated structures, though some are mobile and others operate indoors.

Police and the companies that manufacture and sell acoustic gunshot detection systems claim that the point of this technology is to inform police of the location of shots fired, more quickly and accurately than relying on witnesses who may or may not call the police. However, reports have questioned the accuracy of acoustic gunshot detection, including not registering some actual gunshots, while also erroneously registering loud noises like fireworks as gunshots. This can change police behavior and put people at risk, for example, by sending police expecting gunfire to a location where there is no gunfire but there are innocent people out in public.

Moreover, gunshot detection systems can record human voices–and police have used these recordings as evidence in court. As is so often the case with police surveillance technologies, a device initially deployed for one purpose (here, to detect gunshots) has been expanded to another purpose (to spy on conversations with sensitive microphones).

For reasons such as these, as well as fiscal cost and community backlash, cities like Dayton, Ohio have canceled their contracts for acoustic gunshot detection.

How Acoustic Gunshot Detection Works

Acoustic gunshot detection relies on a series of sensors, often placed on lamp posts or buildings. If there is a loud noise, the sensors detect it, and the system attempts to determine whether the noise matches the specific acoustic signature of a gunshot. If so, the system sends the time and location of the gunshot to the police. Location can be determined by measuring the amount of time it takes for the sound to reach sensors in different locations.

According to ShotSpotter, the largest vendor of acoustic gunshot technology, the automated system’s match between a noise and a gunshot signature is verified by human acoustic experts to confirm the sound is really gunfire, and not a car backfire, firecrackers, or other similar sounds. It’s up to people, listening on headphones, to say whether or not shots were fired.

Who Sells Acoustic Gunshot Detection

ShotSpotter is by far the largest vendor of acoustic gunshot detection systems. Currently, 100 cities are using ShotSpotter in the United States, South Africa, and the Bahamas. The company earned $34.75 million in revenue in 2018, and in March 2019, ShotSpotter announced it would be offering publicly traded stock.

Flock, a company best known for its license plate readers, are now marketing Raven, an audio detection device for monitoring potential gun shots.

Raytheon produces the Boomerang system, which detects small arms fire. It can be mounted on a vehicle and has been used in U.S. warzones like Afghanistan. Other startups, such as Aegis, rely more heavily on artificial intelligence, and visual gun recognition, in recognizing potential shooting situations. Some products, like BodyWorn from Utility, Inc, focus solely on creating gunshot detection for use in schools.

EAGL Technologies is one of the newest companies to enter the gunshot detection market. They claim that their technology is unique because it detects the acoustic energy of a gunshot instead of the audio of a gunshot, though the difference between the two is unclear. EAGL also claims that they can differentiate between handgun, rifle, and shotgun fire with their system. EAGL also manufactures vape pen detection technologies for use in schools and panic buttons which all hook into a central control system.

Threats Posed by Acoustic Gunshot Detection

There are grave concerns about the accuracy of acoustic gunshot detection systems, and especially erroneous conclusions that a gun was fired (“false positives”). For example, a study done by the Chicago Inspector General found that less than 10% of ShotSpotter alerts resulted in evidence of a gun-related criminal offense. In one 2017 case, a ShotSpotter forensic analyst testified that the sensors incorrectly placed the location of a shooting a block away from where it actually occurred. When asked about the company’s guarantee of accuracy, the analyst said, “Our guarantee was put together by our sales and marketing department, not our engineers.”

As Dana Delger, an attorney for the Innocence Project told the Democrat & Chronicle in regards to the placement of Acoustic Gunshot Detection in Rochester, “At the end of the day this is a machine that basically can tell you that there was a loud sound and then a human has to tell you whether it was gunfire or not.”

False positives can cause what may be the biggest threat posed by acoustic gunshot detection: police arriving in an aggressive posture at a location expecting a gunfight, only to find surprised people on the street. As is often the case, police surveillance can cause police excessive force.

False positives can also contribute to wrongful searches and seizures. The Chicago’s Office of the Inspector General also found a pattern of CPD officers detaining and frisking civilians—a dangerous and humiliating intrusion on bodily autonomy and freedom of movement—based at least in part on “aggregate results of the ShotSpotter system.”

Moreover, acoustic gunshot detection systems are often placed in what police consider to be high-crime areas. As with many police surveillance systems, this can result in excessive scrutiny of the neighborhoods where people of color may live.

Finally, this technology captures human voices, at least some of the time. Yet people in public places - for example, having a quiet conversation on a deserted street - often have a reasonable expectation of privacy. People should be free of overhead microphones unexpectedly recording their conversation.

In at least two criminal trials, the California case People v. Johnson and Commonwealth v. Denison, in Massachusetts, prosecutors sought to introduce as evidence audio of voices recorded on acoustic gunshot detection system. In Johnson, the court allowed this. In Denison, the court did not, ruling that a recording of “oral communication” is prohibited “interception" under the Massachusetts Wiretap Act.

EFF’s Work on Acoustic Gunshot Detection

EFF has long raised concerns about acoustic gunshot detection systems, including their recording the conversations of unsuspecting people in public places. In 2021, in light of a number of reports discussing the harmful effects of ShotSpotter alerts on policing and questions about their accuracy, EFF recommended that cities not use the technology.

Suggested Additional Reading

Shotspotter: gunshot detection system raises privacy concerns on campuses (The Guardian)

There’s a Secret Technology in 90 US cities that listens for gunfire 24/7 (Business Insider)